1

HOME > Trends >

WHEN DOES PARODY FASHION ACTUALLY WORK?

THE SHADY WORLD OF DESIGNER-INSPIRED FASHION RECENTLY APPROPRIATED BY HIGH-END BRANDS

Written by Ivan Yaskey in Trends on the 3rd April 2018

We all want to look fabulous, like we’ve got million-dollar taste and the bucks to wear exactly that. Instead, save for the few who see nothing wrong with shelling out a couple thousand pounds for a plain white tee, we’ve got to be creative: Knockoffs a la Canal Street, the shady and sometimes borderline-illegal world of designer-inspired fashion, or parody fashion, a long-standing subsect of streetwear recently appropriated by high-end brands.

Somewhere along the line, we’ve all delved into the former of these three: That Freshjive tee resembling the Tide logo back in the ‘90s, one of those ironic “Comme des Fuckdown” pieces ubiquitous just a few years ago, or many of the Stussy and Supreme styles reworking and deconstructing a well-recognised luxury logo for the skate or surf crowd. The edginess of wearing something possibly – but maybe not fully – illegal has its appeal, but at least in Europe, parody fashion is still somewhat legitimate – provided it’s clearly distinct from the source material, isn’t designed to compete with the original, and isn’t discriminatory.

The U.S. goes by a similar set of rules, but it’s the second out of these three that opens up a whole new door of ambiguity. “Competition” itself is a vague concept, and you can argue that someone searching for a $20 knockoff isn’t in the market for the $2,000 full-priced item. Yet, high-end brands don’t always think so, and at least in the U.S., borrowing or taking inspiration from recognisable logos has led to a few decades worth of lawsuits: Visibly, Dapper Dan for his custom styles in the ‘90s, and Supreme for adding Louis Vuitton’s logo to a skateboard in the ‘00s. Less prominent, Reason Clothing – a parody-based line – has had to pull products, after much bigger brands have alleged Reason’s designs lower their market value. Yet, from thumbing its nose at high-end fashion to its place in certain subcultures, parody has its place, and can be done well.

A Play on Words

This straightforward and usually cheeky take is the most ubiquitous and tends to be the least harmless: Just change around a few letters, keep the same type and design style, and all you end up with is a pun. As some of the most common examples, there’s Brian Lichtenberg’s Homiés tee – based on the Hermès logo – and SSUR’s Comme des Fuckdown graphics – a play on Comme Des Garcons’ wordmark. It’s not particularly deep, nor is it meant to be – just a wink and a nod at high-end brands. Lichtenberg, in a 2013 New York Times interview, even mentioned his strategy stays this simplistic all while paying homage to the brands he appreciates. As a testament to the concept’s overall lightweight character, celebrities have coopted these wordplay tees – Rihanna sporting Lichtenberg’s and Palace Skateboards’, and Cara Delevingne posing in a Bucci tank on Instagram – for a smidge of acceptable street cred.

Making a Statement

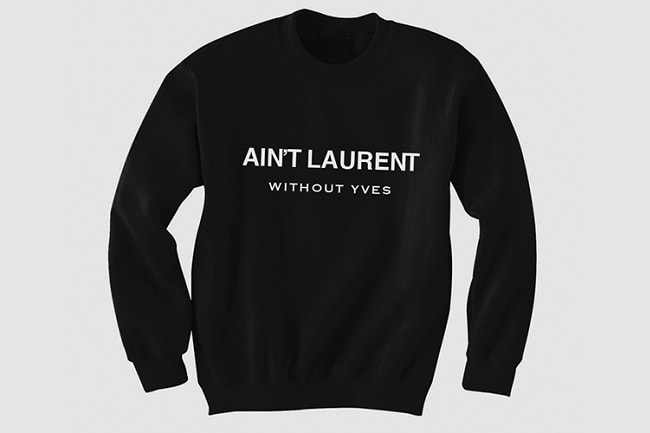

Yet, wordplay quickly transforms into a statement, no matter how trivial. For instance, those “Ain’t Laurent Without Yves” shirts didn’t just borrow the well-known fashion house’s logo; rather, the parody tee came out when the brand dropped “Yves” from the name and coincidentally changed its direction. But, that particular style – which YSL also took action against – takes a fairly tamer route. Reason Clothing and KTHANXBYE, for instance, appropriated similarly definitive logos for social commentary on fashion’s exclusiveness, with Reason altering wordmarks for Dior, Fendi, and Balmain into “Poor,” “Trendi,” and “Nawman,” respectively. KTHANXBYE, meanwhile, is best known for its dirtier take on Cartier’s familiar cursive.

Yet, for brands that have dabbled in parody, commentary on high-fashion’s elitism has long been at the heart of this streetwear subsect. For one, a design mimicking a luxury style is said to partially break down the seeming aura of exclusiveness and let the average consumer take part in the culture to some degree. Secondly, particular to the decade’s hip-hop, skate, and dance music cultures, parody symbolised outright rejection of high fashion – which, if you’re old enough to recall – felt as if it lived in a higher echelon, only overlapping with streetwear to quickly borrow a trend and retreat. High-fashion grunge represented the ultimate offence. As such, plain tees twisted around these supposedly off-limits logos to make a statement.

Taking It Back

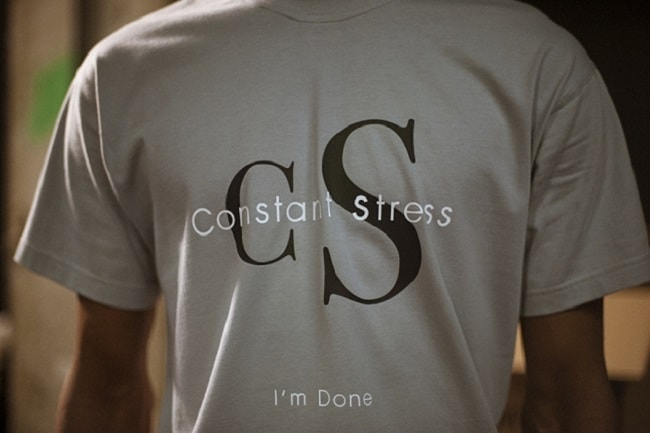

As a predictable response and an outgrowth of high-fashion’s slow embrace of streetwear, major brands started taking back these altered logos. Fashion Week presentations and lookbooks saw Bottega Veneta reuse “Bodega Vendetta” – a reference to Conflict of Interest’s parody – and Vetememes sprang up as an all-out label in response to Vetements’ own parody efforts. Some degree of interplay resulted, with Vetements – already capitalising off parody fashion with its play on the Champion “C” logo – crafting its own response. In some contexts, high-end parody fashion has a place: Take, as an example, last year’s wave of dance music influences. The strongest example, Christopher Shannon’s collection reflected the rebellion of ‘90s rave culture through his wider, draped cuts, bold, colour-blocked palettes, and plays on some of the decade’s most memorable logos. Too, rather than simply be ironic, “Constant Stress” and “Loss” – twists on Calvin Klein and Hugo Boss logos, respectively – embody the frivolous chase of what were the latest trends.

However, Shannon’s addition of context makes all the difference. Vetements and Bottega Veneta, by contrast, appear to almost play a cruel trick in the process of making a clumsy grab at streetwear. The move – worthy of a lawsuit just a decade ago – seems to say “Wait, we’re taking that back,” all while implying their edginess and lack of pretentious. Thus, in the same breath as showing they can take a joke, they remove all the accessibility that’s allowed parody concepts to evolve over the past three decades.

Comme des Fuckdown, Bodega Vendetta, Homiés, Vetememes, Ain’t Laurent Without Yves... would you ever wear Parody fashion? #style

— Menswear Style (@MenswearStyle) April 4, 2018

Trending

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10