1

HOME > Fashion History >

A BRIEF HISTORY OF LONDON SPECTACLES

AN EYEWEAR-MAKING INDUSTRY THAT ENDURED FOR CENTURIES

Written by Menswear Style in Fashion History on the 9th November 2017

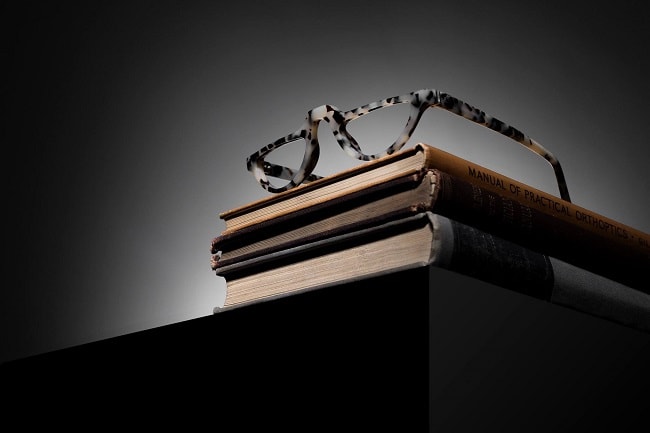

The world’s first spectacles with temples were made by Edward Scarlett in Dean Street, Soho, in 1730. At around the same time, John Dolland, the son of a Huguenot weaver in Spitalfields, was busy creating the achromatic lens, building on earlier work by Sir Isaac Newton of Jermyn Street. These breakthroughs created a spectacle-making industry that endured for centuries, with British optical standards becoming the finest in the world. Spectacle makers Cubitts, have produced a short documentary telling the rise and fall of this once magnificent industry.

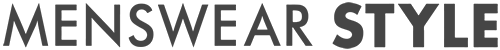

Over centuries, Britain developed a tradition of fine craftsmanship in hand-making frames from more noble materials, mainly gold. Tortoiseshell (or technically turtleshell) gained popularity in the 1920s, and craftsmen became well versed in the art of thin-slicing this beautiful but rare material.

The 1930s ushered in the golden age of design, with the favourite round-eye joined by the rest of the classic British cannon: oval, Quadra and Panto Round Oval - styles which have enjoyed a resurgence in the stylish man’s arsenal over the last few years with more and more metal frames featuring in the coming years. After WWII, factories returned to frame making. But buoyed by a new political urgency and appetite for change, rules were redrawn. In 1948, the National Health Service was established, and one of its key initiatives was to bring spectacles and optics to the masses. During 1949 – 1950, over 200 acetate frames from 90 suppliers were assessed and approved. 10-12 basic styles were approved, with joint, side and bridge variants. These were produced in huge numbers – millions of pairs a year.

Then in 1984, NHS spectacles were abolished, and producers like UK Optical lost their entire business overnight. With limited design and retailing experience, the producers struggled to diversify, and most soon went out of business. And the century ended with Britain a nation of frame retailers, rather than manufacturers. None of the British optical groups retained spectacle making facilities. And of the spectacle makers from a century before, only one remained – the Algha Works in Hackney Wick. In the decades that followed, the industry became dominated by a small number of high-street opticians, driven by clinical necessity rather than aspiration. And the handful of independent British brands looked to international markets to keep their businesses afloat.

But signs of change are afoot. The spectacle, once seen as a mere medical accoutrement, is now firmly an aesthetic accessory. And new breed of opticians is emerging, designing and creating their own frames for an increasingly discerning wearer. Cubitts have just opened the first spectacle-making workshop in London in three generations, offering made-to-measure and bespoke spectacles, alongside their ready to wear range.

“It must be remembered that he had never seen America before, and more importantly he had never seen that sort of tortoise-shell spectacles before; for the fashion at this time had not spread to England. Otherwise the man was exquisitely dressed; and to Brown, in his innocence, the spectacles seemed the queerest disfigurement for a dandy. It was as if a dandy had adorned himself with a wooden leg as an extra touch of elegance.” - Chesterton, G.K. 1926. The arrow of heaven. From the collection The incredulity of Father Brown.

Trending

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10