1

HOME > Trends >

WHAT A POST-STREETWEAR WORLD MEANS FOR MENSWEAR

Written by Ivan Yaskey in Trends on the 4th July 2019

Postmodernism. Post-dubstep. Post-streetwear. Whatever the movement – design, dance music, or fashion – the “post” symbolises the next stage following a revolutionary period that’s forever changed the scene or industry. It implies something better will come along, but what? Will it be more innovative and a successful continuation – a Godfather, Part II, of sorts – or will it be a letdown, of promises and hopes that plateau into mediocrity – the forgettable Part III in this case?

Or, as with post-dubstep, is it boredom and laziness masquerading as refinement? Do you get glitchy yet thin minimalism pushed by trust-fund hipsters with too much time on their hands as a follow-up to the dirty South London sound and Skrillex?

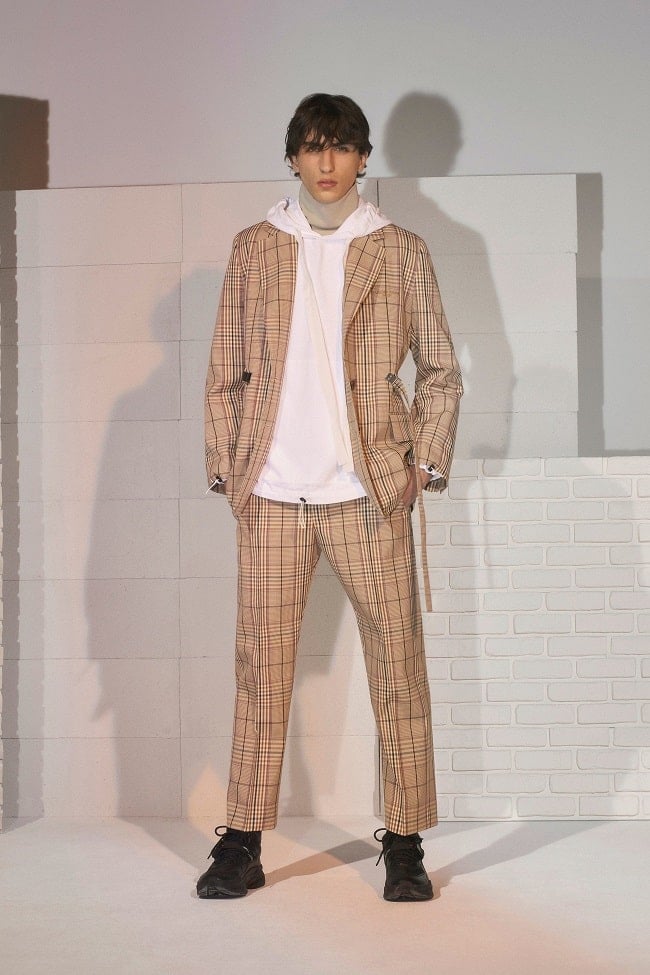

With post-streetwear, the future is unfolding before our eyes. Although fashion publications started tossing around the term in 2017, it’s especially relevant for 2019, the year tailoring supposedly made a comeback. Post-streetwear, though, isn’t just suiting rebranded under a cooler moniker. We’re not suddenly seeing a resurgence of charcoal and navy suits all over the runways. And, if we were, it wouldn’t be called minimalism: Neo-classical – like the early 20th century musical style pushed by Stravinsky – would better describe this turn. Post-streetwear, though, is murkier. In hindsight, we’ll likely view it as a transitional period where streetwear’s foundation remained in the ground, but something else, perhaps borrowing from it liberally, emerged in its place. It could be construed as fashion gentrification, or as repurposing a stagnant trend with no room for growth.

Old, Tired, and Dull

To go back to the analogy above, streetwear and dubstep have followed similar trajectories, beginning underground, shooting up to the mainstream, being appropriated by those who wouldn’t have touched it with a 10 foot pole otherwise, and then hitting a wall constructed through self-imposed restrictions. Dubstep wise, Skrillex marked its big-league ascent, and hearing those wobbly, uneven beats in tracks by Justin Bieber and Taylor Swift back in 2013 marked its oversaturation. Yet, even Skrillex took a break – for collaborative projects Dog Blood and Jack U – and in the aftermath of the dance music subgenre’s popularity, a far more stripped-down version – one allegedly going back to its underground roots – reared its head.

2018, in this sense, embodied peak streetwear. Its ‘90s-referencing silhouettes, pulling from rave and hip-hop cultures, dominated London Fashion Week that year, and over in New York, they turned tailoring into an unexceptional side note. Collection wise, you couldn’t keep up with the collaborations being released, whether it was a one-off shoe or Supreme partnering up with a high-fashion or outdoor brand. The large logos, bold colours, and spacious fits left their mark on everything. And, as perhaps the most been-there-and-done-sign, seeing basic-and-bland celebrities sporting these digs wore away any anti-fashion exclusiveness.

Streetwear, though, dug its own grave. The catch-all term that once described regional-based casual, below-the-mainstream trends – Stussy’s surf-based designs in California, as the oft-given example – and a DIY approach to style lost its lustre and diversity. While, 25 years ago, it encompassed everything from hip-hop, rave, and grunge influenced styles to surf and skate culture to goth and alternative fashions, “streetwear” now implies a specific Instagram-based aesthetic. It’s the kid in a high-dollar graphic tee or oversized sweatshirt, perhaps sporting a Stussy cap or a rare sneaker collaboration. It’s a find shown off, after the buyer purchased it marked up on eBay. And, it’s frequently logo driven: As such, you can take the laziest athleisure silhouette, slap a well-known fashion house’s logo on it, and suddenly, it’s a hypebeast must-have.

A Call to Innovation

Designers aren’t stupid, and last year, Raf Simons – himself both a re-appropriator of and an aspirational force within streetwear – mused about creating a new silhouette. Yet, Simons didn’t lead the charge; for SS19, Virgil Abloh – the very embodiment of a streetwear-to-menswear crossover – crafted his vision of a post-streetwear future for Louis Vuitton. Abloh’s, seeming fantastical with his Wizard of Oz imagery, came out as a hybrid, one built more on a platform of suiting but adorned with streetwear hallmarks. We spotted plenty of wide-legged cuts and fits with a little too much room to be formal, plus monochrome colourways and double-breasted jackets. For old-school streetwear aficionados, it resembled raiding a thrift store to grab a few suits – cuts and fits, be damned – that you later wore out on your board.

Abloh’s template ushered in a new approach for AW19 – a tailoring 2.0 of sorts. Designers strutted out plenty of double-breasted jackets, strong shoulders, and suit-like combinations for this upcoming season, but it wasn’t like watching an Ermenegildo Zegna or Armani presentation from five years ago. Rather, colours stayed far from traditional, and the precise Savile Row fit looked approximate. You wouldn’t show up to a job interview in these digs. But, the question “Are they supposed to be formal?” hasn’t entirely been asked. Revived tailoring implies a return to form, but from Abloh’s SS19 debut onward, this post-streetwear aesthetic comes across as appropriation, too. You can easily picture some ‘90s skater – perhaps the late Justin Charles Pierce from Kids – stealing his parents’ work clothes and finally making them a little less Office Space-y. Essentially, it’s dad fashion that’s less of an ironic eyesore. As well, it’s fairly clear that comfort takes precedence over minimalism and precision. The extra space isn’t just laziness – the suits are cut that way so you can move. Moving beyond the #menswear look of Stan Smiths and rolled up chinos, these approximate fits drape over your kicks like JNCOs.

Classist Hints

The burgeoning post-streetwear movement, however, occasionally comes across as Miley Cyrus disowning her hip-hop-influenced period – of twerking with Juicy J and “We Can’t Stop” – and saying the pop-countrified “Malibu” is her true self. It’s as if fashion went through its own teenage angst-fuelled rumspringa, before committing to the church of tradition. Over at Highsnobiety, Liroy Choufan called out the hypocrisy inherent in this supposed return to tradition, particularly the element of “proper” dressing and sharper, more defined gender roles: “Not only does the ‘proper’ look alienate anyone who isn’t ‘proper,’ it amplifies a ‘correct’ way of being. It’s fitting that Burberry has declared as part of its new PR message that it’s for ‘mothers and daughters, fathers, and sons,’ a phrase that suggests everyone but in fact echoes the traditional family.”

Yet, Choufan further points out post-streetwear’s inevitability: More gendered fashion trends – suits, in this case – tend to gain some ground during periods of cultural turmoil and economic uncertainty. And, while we keep on hearing how great the economy is, Brexit and President Trump’s racist and sexist views trickling down into state-level laws undermine that façade. The fact is, the freedom streetwear implied now comes with a timestamp, and we’re all facing a reality of uncertainty. Thus, if you can suit up – literally and figuratively – and head into the unknown, you’re likely better off than those who can’t.

Trending

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10