1

HOME > Business >

WHY THE LUXURY DEPARTMENT STORE IS BECOMING IRRELEVANT

Written by Ivan Yaskey in Business on the 5th December 2019

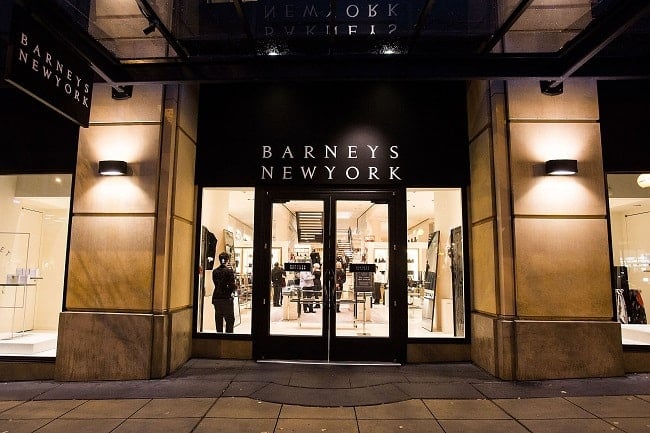

By this point, you’d have to be living under rock to not hear that Barneys – the iconic luxury New York City department store that started as a menswear retailer – filed for chapter 11 bankruptcy and was since acquired by Authentic Brands Group. Although earlier reports claimed that 15 of its 22 stores would close, the acquisition was less hopeful: Authentic Brands plans to close the rest of the remaining Barneys stores, although its namesake is expected to live on in a micro-store-within-a-store concept at Saks Fifth Avenue.

Barneys had been in business for over 90 years, beginning as a strict menswear retailer before shifting over to luxury goods. Its platform helped launch the Armani brand in the late 1970s, and as its reputation and product selection grew over the next few decades, so did its physical footprint. Particularly, the ‘90s saw its brick-and-mortar stores expand in size, but perhaps its approach was too far reaching and too fast. Many today forget that Barneys also filed for bankruptcy in 1998 but got out through the skin of its teeth. The chain spent the next two decades thriving to some degree, although allegations of elitism and racism likely siphoned off a good ideal of its potential customer base.

Barneys’ will-it-survive? saga over the past two months shows that, unless luxury retailers adapt, the customers won’t be there, and the sales simply won’t come. While retail gloom-and-doom reports have focused on many fast-fashion and midrange retailers (think Forever 21’s and Topshop’s recent woes), many have thought the opposite ends of the market – the deep discounters and the luxury brands – to be immune. After all, high-end streetwear and cheaper clothing retailer Primark both seem to have lasted the so-called retail apocalypse. Yet, in spite of KITH’s Sam Ben-Avraham making a bid for Barneys via a social media campaign, the whole effort emphasised just how far behind the times Barneys was. Yes, it was unabashedly elitist, but so is Bergdorf Goodman – a rival U.S. luxury retailer that embraced a store-within-a-store Kith concept. It also didn’t have the versatility of Ben-Avraham’s first effort, Atrium, the mid- ‘90s specialised department store that eventually converted to full-on, standalone Kith stores in 2016.

Atrium, for those too young to remember, pioneered the whole streetwear-as-designer concept over 20 years ago, back when Supreme was still a strictly skate brand. Atrium stores carried Ralph Lauren and Balmain next to traditional streetwear fare, and likely as a byproduct of this juxtaposition, the Kith label eased its way into plenty of collaborations – high fashion to outdoor wear like Columbia. In any case, while Atrium introduced higher-end fashion to the hypebeast who might’ve stayed away, Barneys basically put a “Keep out” sign on its door. While attitude definitely played a role, so have changing retail times. SSense, Mr Porter, Farfetch, and Moda Operandi have cannibalised the digital space Barneys could’ve theoretically laid claim to. Brands aside, shopping on Barneys’ digital site compared to its competitors’ always felt second rate – down to the product detail pages themselves, plus the lack of lifestyle content, like Mr. Porter’s magazine-quality editorial arm. Secondly, rent prices, no matter who you are or what you sell, have been soaring in New York City, plus other major metropolitan areas in the U.S., since the Great Recession, and Barneys, especially for its flagship store made iconic by pop culture touchstones like Sex in the City, just couldn’t keep up. Barneys isn’t 2019’s sole retail casualty – although visibility wise, it’s likely one of the biggest. A Coresight Research report found that 12,000 brick-and-mortar stores will close before the end of the year – double 2018’s amount of 5,864. Particularly where luxury department stores are concerned, here’s where this sector of the retail marketplace is falling behind:

There’s a New Luxury Consumer

Based on recent research from University of Pennsylvania’s Wharton School of Business, the new luxury consumer is someone who researches his purchases and wants a sophisticated, elevated experience. Yet, he’s wary of expensive-for-expensive-sake pricing and prefers off-the-beaten-path speciality retailers to massive department stores. He’s the type to look off Madison Avenue in New York and find that designer setting up shop in Seven Dials London. He’s also someone who’s flown in from overseas and wants an upscale, curated shopping experience. At the same time, the modern consumer doesn’t really window shop anymore. Although he or she will visit a brick-and-mortar location, they’ve got their smartphones out to comparison shop – and may even seek out reviews or ask for friends’ and family members’ opinions in the same session. Added to this, the in-store experience might just be to feel or try something on. If the item’s priced lower at a competitor (or at a smaller speciality retailer), the luxury customer still goes where the best deal is. On the other hand, Retail Dive's Consumer Survey indicates that men, young to old, would rather buy directly from brick-and-mortar to take something home that same day. On this note, stores that don’t allow users to buy online and pick up in store – even for luxury goods – wind up missing a key potential customer segment.

Diversified Retailers

Luxury department stores are facing competition from multiple fronts that make the traditional model nearly obsolete, unless they can adapt to changing tastes, a la Bergdorf Goodman. On the experience end, speciality, single-brand stores simply do it better. A customer, say, seeking out Louis Vuitton clothing or even a Canada Goose jacket knows that the associates in a branded store often have in-depth knowledge about the products sold there. By comparison, department store sales associates often go by general information, or might not be thoroughly familiar with a particular brand. Added to the points above, the luxury customer wants the retailer to supplement his research. As an extension of this notion, speciality stores have expanded the lifestyle experience in recent years – think Ralph Lauren’s restaurant or Red Wing’s shoe support selector – and these facets get cut when a large retailer has to cover a greater swath of brands. On this last note, digitally native retailers – that is, brands who started online and expanded to brick-and-mortar – are predicted to outpace the growth of traditional retailers. A study by Retail Dive found that, up to 2023, digitally native brands will be behind 850 new stores. Although numerically it’s below the 3,000 new stores traditional brick-and-mortar retailers opened in 2018, realise that 7,000 brick-and-mortar stores also closed up shop over this period – and much of its growth was concentrated in the discount sector.

At the same time, many mid-to-high department stores have found success with off-price and discount models in recent years – think Macy’s Backstage or Nordstrom’s Nordstrom Rack going brick-and-mortar. Although these arms don’t replace the dominant business model, they attract a new subsect of customers wanting a deal on designer brands without compromising quality – even if the selections are limited and less organised. As the third factor – and likely a significant blow to Barneys and its ilk – the luxury sector has finally caught up to eCommerce technology. In turn, brands that would’ve sold almost exclusively through a large department store – think Fendi, Gucci, and Hugo Boss – have their own buy-direct sites – often with the whole lifestyle experience rolled in. As a counterpart to this, Mr. Porter, SSense, Farfetch, and Moda Operandi redefine the whole notion of massive luxury selection, and frequently complement styles right from the runways with their own quality in-house brands. And, for consumers who can’t afford these prices, luxury resale websites like The RealReal or Thrift+ couple authentication with lower, somewhat more affordable prices.

Millennial Shoppers are Overtaking Baby Boomers

Even once you get all the “Ok Boomer” memes out of your system, one factor still stands: Demographics on both sides of the pond are changing, and that’s altering shopping habits. Yes, Millennials – and their Gen Z cohorts – might have been the nail in the coffin for certain brands, but they’ll also look for and buy brands regardless of where they’re being sold – department stores, online, or speciality retailers. The fact is, the Millennial generation is growing up, their numbers have surpassed the Boomer generation, and they’re at the point where they have the cash to purchase homes – or put it toward luxury goods. Along this line (and plenty of content marketing collateral), Millennials want a narrative with their product. They’re looking for origins – history and craftsmanship, but also if it’s sustainable – and want a brand’s values to be in line with their own. As such, luxury brands that come up with a story and adapt to changing tastes – for instance, Gucci’s more unisex offerings or Carhartt WIP – end up resonating with this growing group of consumers.

Trending

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10