1

HOME > Tips & Advice >

A GUIDE TO UNDERSTANDING VEGAN LEATHER

Written by Ivan Yaskey in Tips & Advice on the 7th January 2021

You may have read the studies showing how the consumption of animal products negatively impacts the planet, extending from meat to leather. As such, it only seems logical to switch from traditional animal-based materials to vegan leather. Reflecting this, a study from Edited last year found that the number of “vegan” products being sold in the UK increased 75 percent from 2018 to January 2019. At the same time, Grand View Research estimates that the market for vegan leather alone will be worth $85 billion by 2025 – up from its current value of $25 billion.

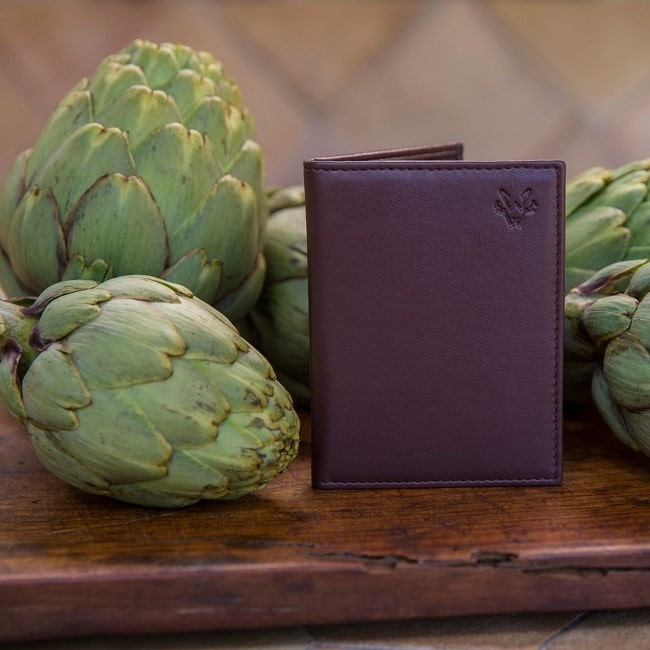

Yet, vegan leather isn’t regulated or quickly defined. With higher-end items, like Stella McCartney’s bags and apparel, you could end up with a proprietary hybrid that’s partially biodegradable but also uses some polyurethane (PU). With fast fashion, an increasing number of brands turn to PU or still use the older PVC – neither of which are biodegradable nor recyclable. A third and gradually growing category repurposes fruit and vegetable waste, transforming it into textiles for a more sustainable and biodegradable alternative. Back in 2018, multiple higher-end brands including Versace, Gucci, Burberry, and Coach started banning fur from their offerings, but as vegan leather gains some steam, many are wondering if it’s truly a viable alternative or equally as polluting as the leather industry.

Types of Vegan Leather

Vegan or synthetic leather goes by a flurry of names. Back in the late ‘90s and early ‘00s, it was known derisively as “pleather” – as in plastic leather – and its obvious fakeness and artificiality was mocked for at least a decade. Particularly where shoes are concerned, you’ll see synthetic leather products using PU, PVC, or leatherette, and then, especially with higher-end fashion, you’ll run into several proprietary material names. The history of leather alternatives stretches back over a century. Toward the end of the 19th century in Germany, Prestoff, made of layered paper pulp, was invented in response to a leather shortage and briefly used for bags, belts, and other ordinarily leather-based products. While Prestoff never caught on, Naugahyde – the first mass-produced synthetic leather – had a longer lifespan. Produced by the US Rubber Company in the 1920s, it looked like leather and offered greater durability than Prestoff. Starting in the 1960s, polyvinyl chloride, more commonly known as PVC, entered the market as a synthetic leather alternative. Because PVC is naturally hard and less flexible, it requires plasticizers to soften its composition. For more flexibility, PU has started surpassing PVC, often starting with a textile base for flexibility and featuring a polyurethane coating on top.

Yet, both PU and PVC are still plastic-based products. As more brands think about sustainability, the less environmentally friendly these alternatives look, both in terms of how they’re produced, their lifespan, and their contribution to the global waste problem. From this issue, plant-based vegan leathers have started to emerge, made from apple peels, pineapple leaves, mangos, corn, mushroom, or cork. While these don’t require the chemicals to produce PVC or PU, their production is significantly more complicated, and this aspect is often reflected in the price. These solutions, at least in visual appeal, tend to last longer, offer greater breathability, and develop an aged appearance with time, while PU often has a shorter lifespan and cracks rather than develop a worn patina. In this regard, some of the materials you’ll come across include:

- Frumat, made of apple waste and PU.

- Piñatex, a material developed by Ananas Anam made of pineapple leaves sourced from the Philippines.

- MuSkin, made of fungus Phellinus ellipsoideus, which is then treated with an eco-friendly wax.

- Mirum, a fibrous material developed by Natural Fiber Welding using cork waste, hemp, coconut, and vegetable oil.

- Cork, which can be processed to feel like leather and is fully recyclable and biodegradable.

- Vegetable oil-based leather, like Stella McCartney’s Eco Faux Leather, replaces petroleum in the PU production process with a vegetable-based alternative that breaks down sooner.

- Microfiber-based materials like Vegetan and EcoLorica start with a fibrous material, which is then coated or soaked in a resin for strength against the elements.

Why Vegan Leather Can Be Problematic

Vegan leather might result in the consumption of fewer animals, but the process traditionally hasn’t been eco-friendly. PVC, the oldest version of faux leather in rotation, is particularly concerning: Phthalates – which can be highly toxic – are used to soften the material and make it more pliable. For this reason, Greenpeace has called PVC the “single most environmentally damaging type of plastic.” Yet, the damage PVC does exist beyond manufacturing: During its lifespan, it leaches out the phthalates and other toxic fumes, including dioxins and BPA, both of which may be behind reproductive and developmental health issues. Due to this process, certain phthalates going into PVC’s construction have been banned. Polyurethane, or PU, is a less-damaging solution, but that doesn’t mean it’s environmentally friendly. While PU often starts with a woven fabric base, for years, it used an oil-based polymer, which, as with other petroleum byproducts, takes centuries to break down. Newer versions of PU have started addressing this process by using a waterborne coating instead, but even this aspect doesn’t take into account the manufacturing process for creating PU. Neither plastic-based material breaks down fully, and both the production behind them and their presence continue to pollute the environment.

Is Real Leather Any Better?

Due to the greater market share vegan and faux leathers have started to consume, the leather industry has been on the attack, taking and running with this last point: Particularly, that real leathers, made from cow or other animal hides, will eventually break down and are therefore more environmentally friendly. However, this aspect is just a sliver of the process involved in creating leather, and in fact, studies have shown that, at least in manufacturing, natural leather continues to have a larger, more negative impact than synthetic alternatives. To break it down, the tanning process is energy intensive, casting a greater carbon footprint, and involves mineral salts, coal-tar byproducts, various oils and dyes, and formaldehyde. Some of the solutions, at least historically, have contained cyanide. Once the process is done, the waste from a tannery contains sulfides, salts, acids, and lime, which, until recently, were dumped into rivers and other water sources, rather than disposed of properly. These byproducts also enter the air of communities surrounding a tanning facility and impact the health of its citizens, including increasing cancer risks. As well, while animal hides frequently come from cattle raised for beef and milk, the process of clearing land for livestock contributes to deforestation and that’s not counting the cruel practices involved in their slaughter. To illustrate leather’s sustainability, the Leather Working Group (LWG) started assigning Gold and Silver ratings for more transparency regarding practices.

As a newer solution, Vogue Business reported on bio-fabricated leather: essentially, real leather made out of collagen, right now going by the name of Zoa. The product has yet to hit the market, but its creation is expected to assist with lessening natural leather’s environmental impact without reducing its strength. As another strategy, vegetable tanning has started replacing the traditional chemical-based process with more biodegradable solutions. Still, the natural leather industry has a long way to go. In 2018, Kering released its Environmental Profit & Loss report showing that the production of vegan leather is one-third more sustainable than natural leather. The report takes into account emissions from livestock and agriculture, water use, and the industry’s impact on biodiversity, the usage of heavy metals in tanning and dyeing, and how these processes contribute to the growth of algae, which can choke off oxygen in waterways and reduce species populations. However, the ramifications of synthetic materials cannot be ignored: Here, vegan leather takes longer to degrade, contributes to microplastics entering the oceans and food chain, and still requires water, energy, and chemicals to be produced. Collectively, while vegan leather might cut down on animal consumption, it’s a good idea to do your research into the material itself and its production process before you purchase an item and support a brand.

Trending

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10